Will EU–Mercosur bilateral safeguards really matter?

With this week’s discussions on upgrading bilateral safeguards under the EU–Mercosur Partnership Agreement, it is worth revisiting a point I have raised before. Public discussions on Mercosur raise legitimate concerns, but these are not always accompanied by a detailed assessment of market data or of the agreement’s operational mechanisms. This piece aims to bring the discussion back to numbers and trade dynamics.

The safeguard mechanism is designed to suspend tariff concessions if imports of sensitive agricultural products both surge in volume and undercut price levels in the European market. At first glance, this approach mirrors safeguard systems found in other EU trade agreements, including those with Chile, New Zealand and Japan.

It is like a travel insurance: reassuring by design, but ideally never to be used. Below, I explain why, based on existing quotas and price structures, the conditions required to trigger these safeguards are unlikely to materialize – which is good news for farmers !

What’s new in the safeguard mechanism?

The bilateral safeguard formalises an existing provision allowing the suspension of market access if imports “harm or threaten to harm” EU producers. What is new is the automatic triggering mechanism: investigations would be launched when both conditions are met:

Import volumes increase beyond a defined threshold (originally proposed at +10%, still under discussion),

Import prices fall relative to EU market levels (originally proposed at –10%, also under discussion).

Why these conditions may not be met

Two structural features of EU–Mercosur agricultural trade make these triggering conditions unlikely for most sensitive sectors:

Tariff-rate quotas for sensitive products are generally set below current import levels from Mercosur, and

Mos sensitive Mercosur exports (beef and poultry) are priced above EU market price averages, limiting the scope for price undercutting.

Sectoral overview

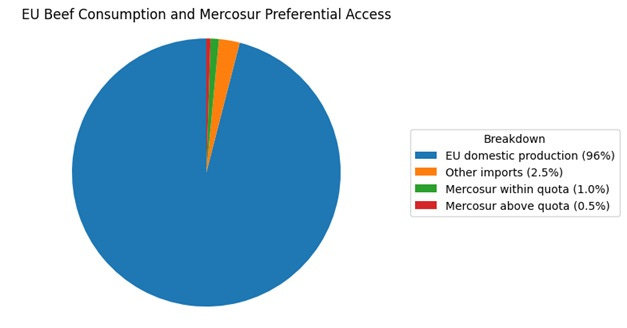

🐄 Beef

Preferential tariffs apply to only around two-thirds of current Mercosur exports to the EU; any additional volume faces full tariffs.

In 2024, Mercosur beef exports to the EU were, on average, priced at roughly twice EU market levels, making price-driven displacement unlikely.

With tariff-free access capped below existing flows, there is limited scope for a volume surge.

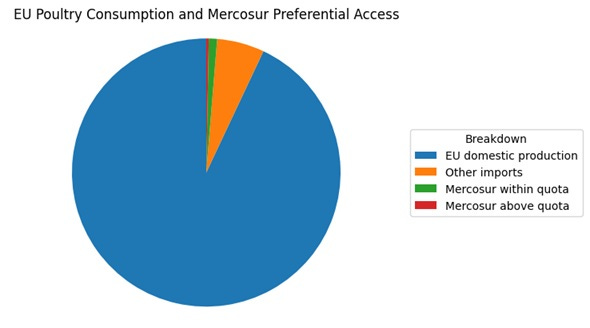

🐔 Poultry

Preferential access covers about 78% of current EU poultry imports from Mercosur; volumes beyond that face full tariffs.

Mercosur poultry exports are around 20% more expensive than EU prices on average.

As with beef, the quota structure imposes a natural ceiling on expansion.

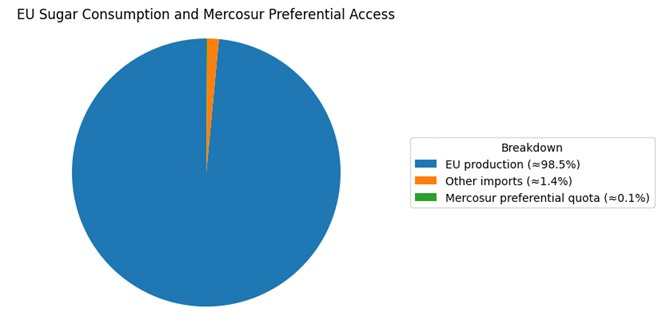

🍬 Sugar

For Brazil, sugar will be integrated into the EU’s existing WTO in-quota system.

No meaningful change in market access is expected.

Paraguay’s quota amounts to 10,000 tonnes, or 0.06% of EU production—economically marginal.

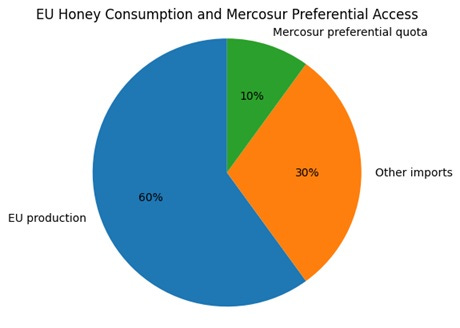

🍯 Honey

The EU produces only around 60% of its honey consumption and relies on imports.

Preferential access under Mercosur would cover about 10% of the EU market, a limited share unlikely to be disruptive.

🍚 Rice

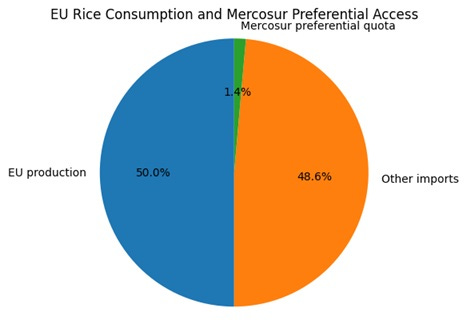

The EU is a net importer, with domestic production covering about half of demand.

Preferential access for Mercosur would cover just 1.4% of the EU market, benefiting only 28% of current Mercosur imports.

Bottom line

EU–Mercosur bilateral safeguards are tightly designed, activating only in cases of simultaneous volume expansion and price compression. Yet, existing quotas and prevailing price structures already constrain both. In practice, they function less as a brake on trade and more as a reassurance mechanism.